Morphodynamic evolution following sediment release from the world's largest dam removal

January 10, 2019Ritchie AC, Warrick JA, East AE, Magirl CS, Stevens AW, Bountry JA, Randle TJ, Curran CA, Hilldale RC, Duda JJ, Gelfenbaum GR, Miller IM, Pess GR, Foley MM, McCoy R, and Ogston AS. 2018. Morphodynamic evolution following sediment release from the world’s largest dam removal. Nature Scientific Reports 8:13279.

In a nutshell

- Removal of two mainstem dams on the Elwha River in Washington State is the world’s largest river restoration project and a unique natural experiment

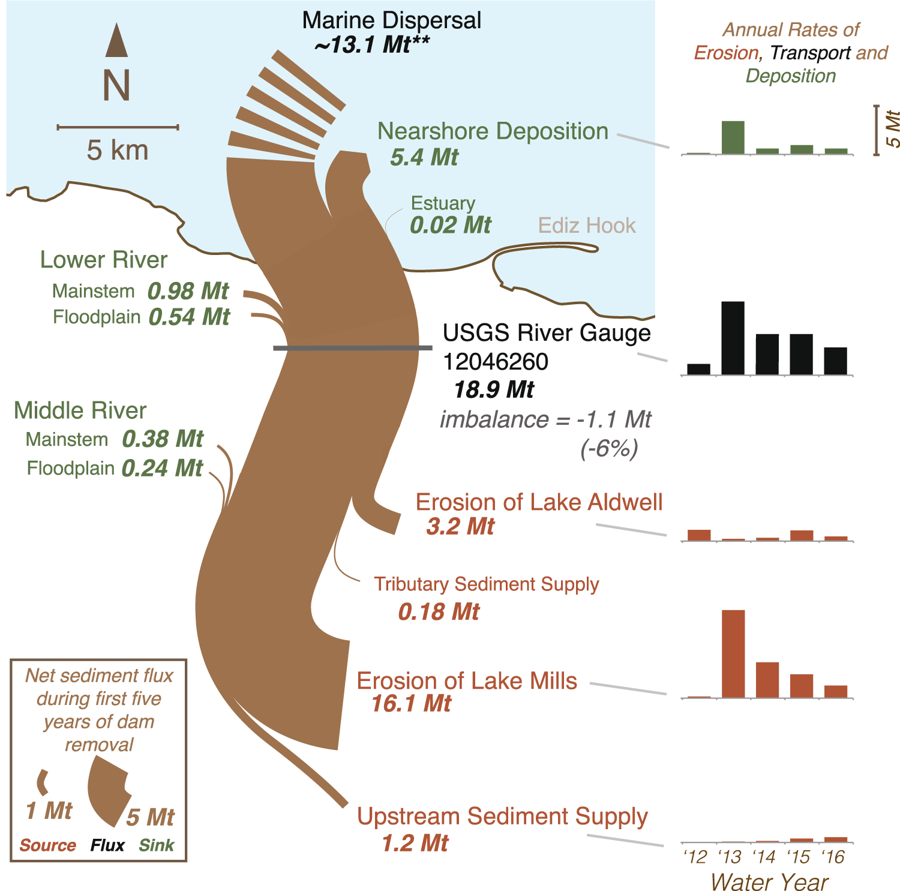

- Breaching of the dams released more than 30 million metric tonnes of sediment following phased removal of the dams, which redistributed across the flood plain and into the estuary

- The Elwha River efficiently carried the sediment downstream, with sediment flux and turbidity falling after an initial 1-2-year pulse

- Re-establishing flow from upper reaches brought logs and large debris to middle and lower reaches, contributing to evolution in river morphology and habitat development beneficial for salmon

- Sediment deposition at river mouth built the estuary by around 60 ha and turned a stony steep beach into a large sandy estuary that provides new fish and shellfish habitat

- Salmon were found in the upper river in the first season after dam removal, illustrating salmon’s ability to colonize new or newly connected habitat

- The initial recovery of both biological attributes and physical features of this river was remarkably fast and provides a clear demonstration of the efficacy of dam removal as a restoration strategy

Dam removal from the Elwha River in Washington State between 2011 and 2014 is the largest restoration project of most peoples’ lifetimes and a unique opportunity to study the impact of a massive pulse of sediment following flow restoration on a river ecosystem. Researchers found that not only did the sediment previously trapped behind the two dams flush through surprisingly quickly, but it also altered downstream river geomorphology, and restored river dynamics that can help create and maintain salmon habitat.

Methodology

The research team used traditional river survey tools such as USGS stream and stage gauges to monitor river dynamics. They also used LiDAR and aerial survey to create high-resolution 3D maps to follow changes in river geomorphology. Lead author, geomorphologist Andrew Ritchie with the Pacific Coastal Marine Science Center, notes that due to the predictable nature of the event, the team could gather a lot more data before sediment release.

“One of the unique aspects of this event is that we knew it was coming,” he comments. “Researchers were able to collect thorough pre-disturbance measurements (of some parameters). Because of that, we’ve been better-equipped to show just how quickly the main disturbance pulse passed.”

During the second year of dam removal, the sediment pulse peaked at more than 70 times the estimated normal levels handled by the river. Despite this and lower than average seasonal flow, the river rapidly and efficiently transported sediment downstream and out to sea. Although during the 5-year recording period (water years 2012–2016) some was retained within the river system (~10%) and at the estuary (~26%), the majority was transported offshore. Sediment release and return of river continuity also altered the landscape, changing the downstream course by increasing its twists and turns. Once the sediment pulse had passed, the river eroded through the deposits to form more stable channels. As a result, Ritchie describes an improvement in spawning gravel quality in lower and middle river with the river bed now comprising more than just large cobble.

Recovery – Fish Stats by the Numbers

Since there was no provision or requirement for fish passage at the time they were constructed, the dams blocked more than 90% of salmon spawning habitat for almost a century. With 70 miles of river unreachable, anadromous fish populations reduced by 98%.

Apparently though, the fish were just waiting for a way through.

In the first season post-removal, The Seattle Times reports that 4,000 Chinook salmon spawners were found above the Elwha Dam site (removed March 2012), and Elwha Chinook salmon swam past the upper dam site at Glines Canyon within three days of its removal in September 2014. By 2014 in the middle river, coho fry increased from zero to 32,000, and steelhead increased 300% between 2013 and 2015. Chinook spawning nests (redds) increased by 350%.

In 2016 (five years post-removal), the fish population was at its highest for 30 years and ocean-going species were once again appearing in middle river reaches.

The released sediment was also associated with a massive expansion of the estuary. Ritchie notes that packs of sea lions hang around for much longer since the dam removal, and eagles by the dozen. Families enjoy the sand on sunny weekends more often, where once only diehard surfers would venture.

Equilibrium?

Although it will take many more years of study to establish if the river has reached a new equilibrium, the initial results suggest that conditions in the Elwha are returning to the characteristics of free-flowing rivers in the region.

The speed of its response to dam removal is however, a surprise. George Pess, co-author and Watershed Program Manager with NOAA Fisheries, comments that the results show recovery can be faster than previously hypothesized.

“This large-scale restoration measure allows us to understand that large-scale habitat restoration can result in more immediate, positive changes than initially hypothesized. This means that both salmon spawning and rearing habitat can re-establish soon after the initial impacts, as well as increase in both area and quality for the long-term.”

Restoring river continuity also brought large wood debris downstream from upper reaches. The new log jams and the sediment deposition have created prime fish real estate.

Research Impact

In summarizing the study’s impact, Pess suggests that the results show how complex river and coastal ecosystems can respond rapidly to dramatic changes.

“Our findings, along with the design of this project (to let the river move the sediment instead of thousands and thousands of dump trucks) should encourage people to think of creative ways to use natural systems solve problems created by our failure to understand their complexity. Nature can be a powerful ally or an insurmountable foe, depending on your relationship with her.”

With the Elwha showing much faster recovery than expected, results from the world’s largest dam removal could help encourage similar restoration projects.

Science Spotlight by Amanda Maxwell